History and memories sometimes act like anchors, steadying the ships to a rest, but sometimes they need to be dusted off.

—Wang Ning-De

Interview by Wei-I Lee

本文出自《VOP攝影之聲》#5,2012年

VOP __ Time, history and memories have always been the topics of your photographic creations. Why did you choose to come face to face with these topics? What’s the background behind the creation of “Some Days”?

Wang Ning-De __ “Some Days” began in 1999, when people were rushing forward in the fast-changing era, and I was no exception. History and memories sometimes act like anchors, steadying the ships to a rest, but sometimes they need to be dusted off, especially to those –like me– whose minds are filled with lies and deceit. Dusting it off will reveal the truth, and the true color of things without covering up the ugly parts. To me, I believe that it’s a painful but necessary process of healing, as well as an attitude of resolute. “When everyone is looking forward to the future, somebody has to look back”; only then will the whole community be more balanced and orderly. Hence the background to “Some Day” is thinking, anxiety and the process of metamorphosis.

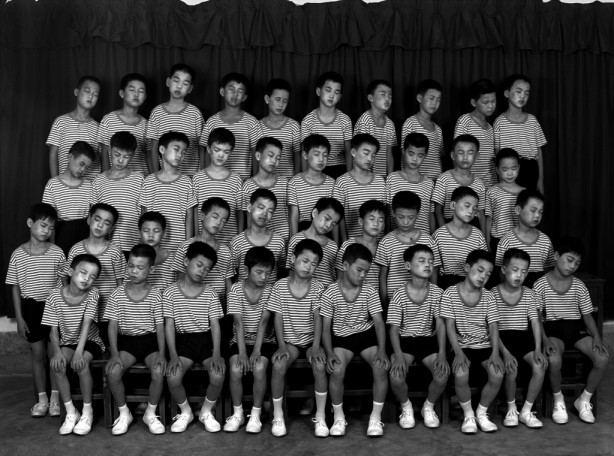

VOP __ In “Some Day”, all the characters seem to live in a daydream of a collective memory; their attire, appearance and postures seem to stagnate in a particular era. Some characters have their eyes closed, as if they are sleeping or sleep-walking, or even avoiding something. Even when there are animals, they turn their backs to the camera. Why is it so?

People’s eyes are either closed or opened—of course, you can also add in half-opened. There are so many images in the history of photography with characters with opened-eyes, mostly a result of what people think good photographs should be like. However, I’ve already given up taking “good pictures” many years ago. Actually, there are many important facial expressions of people that are with closed-eyes—in fear, sleep, death or a dream-state, and even during sex. “The eyes are the windows to the heart”, but I dream to present to my readers a building with its windows shut.

VOP __ This reminds me of the fact that memory itself is invisible. Some scenes in “Some Days” are of everyday life, some are without any clues to their backgrounds, just like in a dream. Does your choice relate to how you look at memories?

I often use writing as an example to the structure of a series of works. In this structure, every paragraph and every part has its own function—they can be individual sentences, but at the same time they relate to and influence each other. Eventually, this influence will affect each piece of work and adds depth to it, which will show when the audience reads it.

Since I am replicating memories instead of history—or rather, freezing memories in time—it’s necessary to differentiate what’s real and what’s not. Whether a piece of memory is real or not is not determined by whether its background is of everyday life or without anything solid; memories set in the real, everyday life may be made-up, but scenes that are set in backgrounds as beautiful as in dreams may very well be real.

VOP __ Does the person in a Mao suit point to the memory of a particular period of history?

I purposely blurred the specific time frames that the pictures might point to when I named them; even though this is a series that is related with memories, I still hope that the pictures could expand to include wider and deeper spatial and time frames. Only then will they include time itself in the topic, not just stopping at a particular period of time. The man in the picture is wearing a Chinese tunic suit which is the formal attire of all Chinese men when I was young, which also signifies order and patriarchy.

VOP __ Are order and the patriarchy important elements of your memories?

Yes, they both are. I hope that the patriarchy I have used here would have a wider meaning to include violence and power.

VOP __ People always choose what they want to remember, be it good or bad, personally or collectively. Similarly for photography, the memories that images capture are always constructed, yet discontinuous. Even though nowadays we still depend on photography to verify or as evidences for what has happened, we are well aware that “stories” could be told from photographs instead of facts. What are your thoughts on the point that photographs could be seen as evidences of history or the re-presentation of memories?

Wang / When I started working on “Some Days”, I was already very sure that I wasn’t recreating history, but exploring “memory” itself. As we dwell deeper into memories, we become more aware that memories are not reliable as it can be changed and influenced easily. Therefore memories that are from a single person’s point of view then becomes very valuable. It’s not like a CD or a hard disk, which will show the same files every time you click them open—it’s more like a paper, which changes little by little every time you take it out to read, which oxidizes and yellows as time passes, and finally turns into dust. What kind of memories then are the most accurate? The answer is “now”. Therefore, we have to freeze them in time before the memories change too much, instead of recreating the truth. Once things happened, it won’t be in its original state anymore. Hence I wasn’t recreating the past, but recreating memory itself—until the images themselves become memories themselves.

VOP __ Many contemporary artists are skilled in handling the many sensitive issues that China is facing now. Yet some parts of history are ignored or unexplored, which may perhaps be the most sensitive parts of those memories. What do you think is the part(s) of memory that China is most unwilling to face?

What China is most unwilling to face is perhaps what we want to understand most but know the least. From this point of view, we aren’t avoiding memories, but are forced into amnesia. This consequence makes us all embarrassed and in despair. Personally, what I am most unwilling to see is a memory that is “edited” or “enhanced”—it’s crude and fake, and I’d avoid it at all costs.

Wang Ning-De, born 1972 in Liaoning Province, China. Graduated from Luxun Academy of Fine Arts, he majored in photography and worked as a photographer for the press. He now lives and works in Beijing.

王寧德,1972年生於中國遼寧省,1995年畢業於魯迅美術學院攝影系,曾任報社攝影記者,目前在北京工作與生活。